Virtual Reality Is How Reality Reaches You

23 Nov 2025In Chapter 5 of The Fabric of Reality, David Deutsch pushes his criterion for reality to its limit with a thought experiment:

Suppose that you lived inside a virtual simulation. What, if anything, in that situation should you regard as real?

As I understood it, he’s aiming at two outcomes:

1. To soften the distinction between “real” and “virtual”.

He wants to show that experiences in a virtual world are still grounded in complex physical processes (like computers and brains), and so they shouldn’t be dismissed as “not real”.

2. To make a deep claim about our universe.

The very fact that virtual reality is possible at all is, for Deutsch, a fundamental feature of the fabric of reality.

At the end of the chapter, he argues that this fact connects computation, human imagination, art, science, mathematics, and fiction. (p. 122)

What is Virtual Reality?

According to David:

“virtual reality [is] any situation in which the user is given the experience of being in a specified environment” (p. 122)

He then makes four key distinctions to define virtual reality:

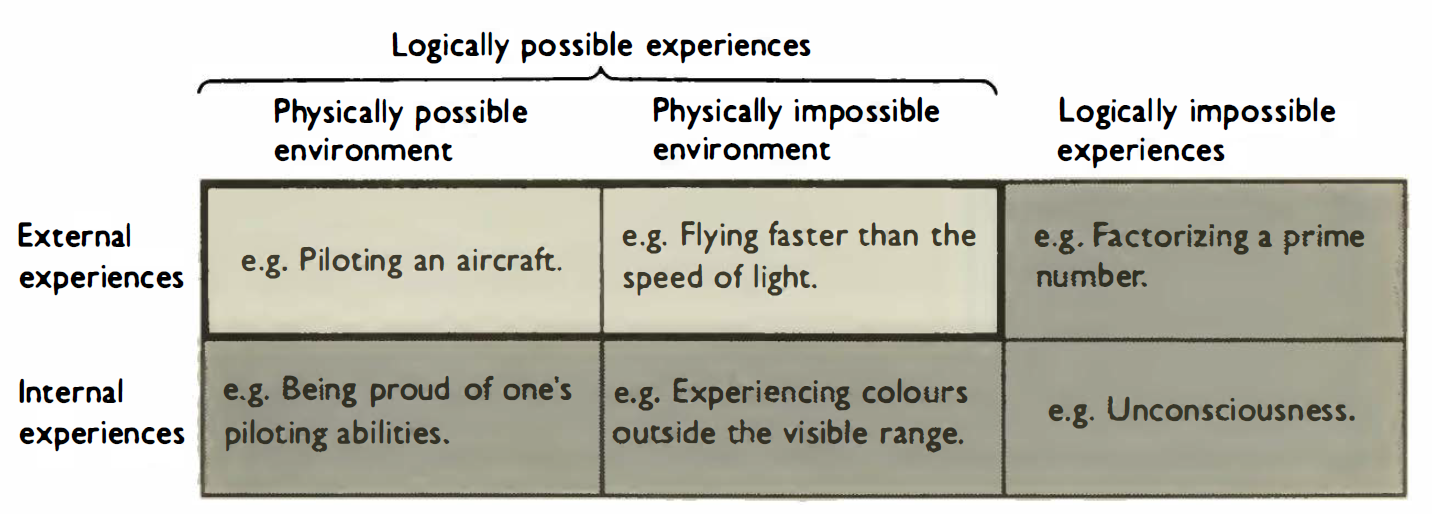

-

Logical impossibilities are excluded: A virtual reality cannot make contradictions true. For example, you might believe to factor a prime number in VR, but since that’s logically impossible, you have not really done so.

-

Internal experiences are also bound by logic: Virtual reality cannot produce logically impossible internal states in a mind (for instance, being unconscious while experiencing something).

-

Physics can vary, logic cannot: A VR can present both physically possible and physically impossible environments (i.e., with different laws of physics or cheat codes), as long as everything that happens in them remains fundamentally logically consistent. And “physically possible”, in his sense, means “allowed by the actual laws of physics” – in the multiverse picture from earlier chapters, that is: environments that exist or could exist in some branch of reality.

-

The mind is not fully controlled by VR: VR generates external experiences, but it does not fully determine a person’s internal mental life (thoughts, interpretations, decisions), which remain partly autonomous.

These distinctions lead David to define virtuality as “the generation of logically possible, external experiences (top-left region of the table)” (p. 105).

Virtual Reality as Predictive Theory

Once David has described as virtual reality as “the generation of logically possible, external experiences”, he explains that, in principle, VR simulators can be made arbitrarily accurate - indistinguishable from ordinary experience.

He argues that, in principle, we could eventually connect directly into a person’s brain and deliver a simulation that is complex and autonomous - one that “kicks back” when the user acts, which is what justifies calling it a reality in “virtual reality” (p. 113).

In such a simulation, VR:

“does not mean specifying what the user will experience, but rather specifying how the environment would respond to each of the user’s possible actions” (p. 113).

A VR that runs autonomously and “kicks back” has to encode deep explanatory structure, not just a lookup table of predictions. Otherwise it can’t respond correctly to arbitrary user actions.

In 1997, he is effectively describing the kind of full-immersion simulations later popularized by films like The Matrix and The Thirteenth Floor (both released in 1999).

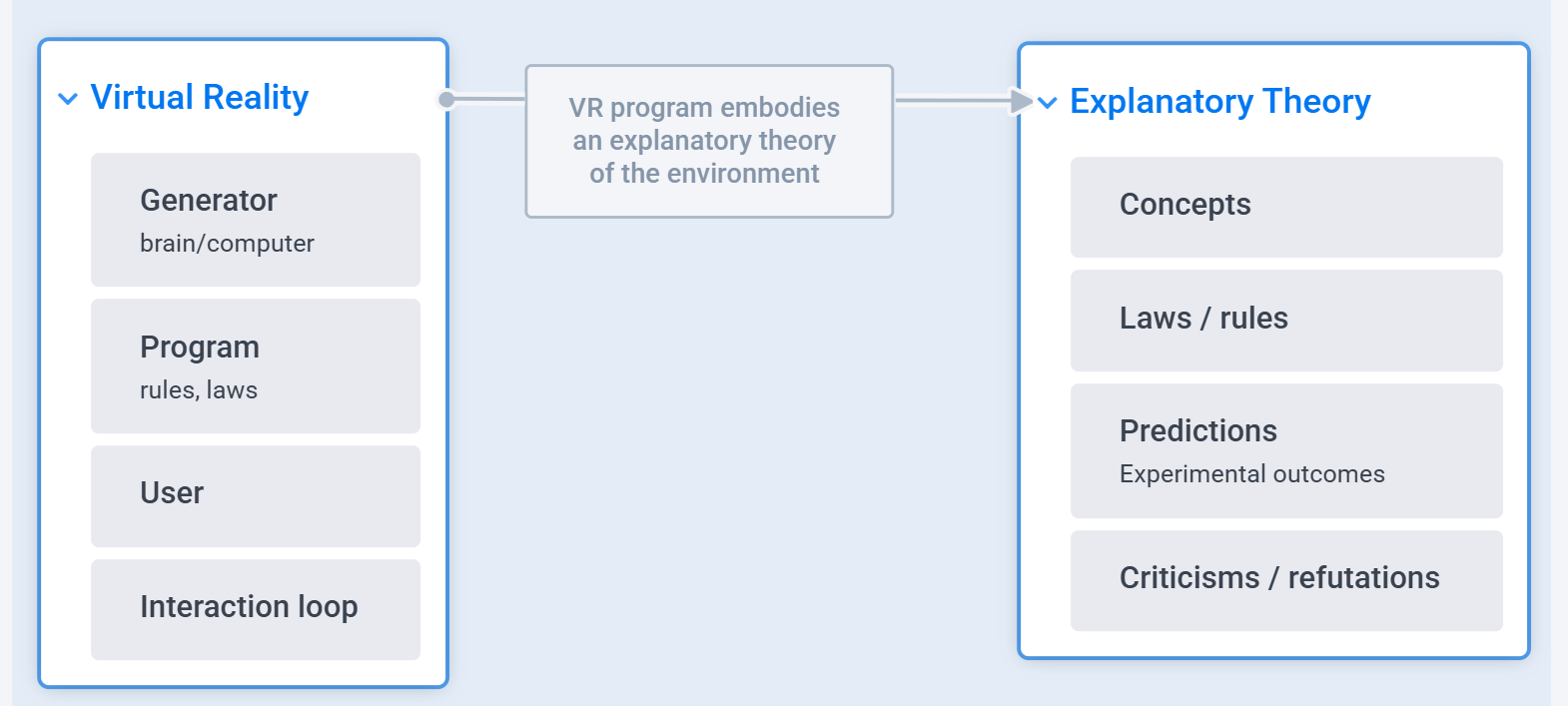

On page 117, David links explanatory theories and virtual reality. You cannot build an accurate VR without first having an explanation of the relevant laws (logic, physics, etc.). Therefore, a VR program is itself a predictive theory.

Here’s a breakdown of his argument line by line:

Premise 1: The program in a VR generator embodies a general, predictive theory of the behavior of the rendered environment.

Premise 2: Thus, if the environment is physically possible, rendering it is essentially equivalent to finding rules for predicting the outcome of every experiment that could be performed in the environment.

Premise 3: Because of the way in which scientific knowledge is created, ever more accurate predictive rules can be discovered only through better explanatory theories.

Conclusion: So accurately rendering a physically possible environment depends on understanding its physics.

He then flips the direction of the argument:

“discovering the physics of an environment depends on creating a virtual-reality rendering of it” (p. 117-118)

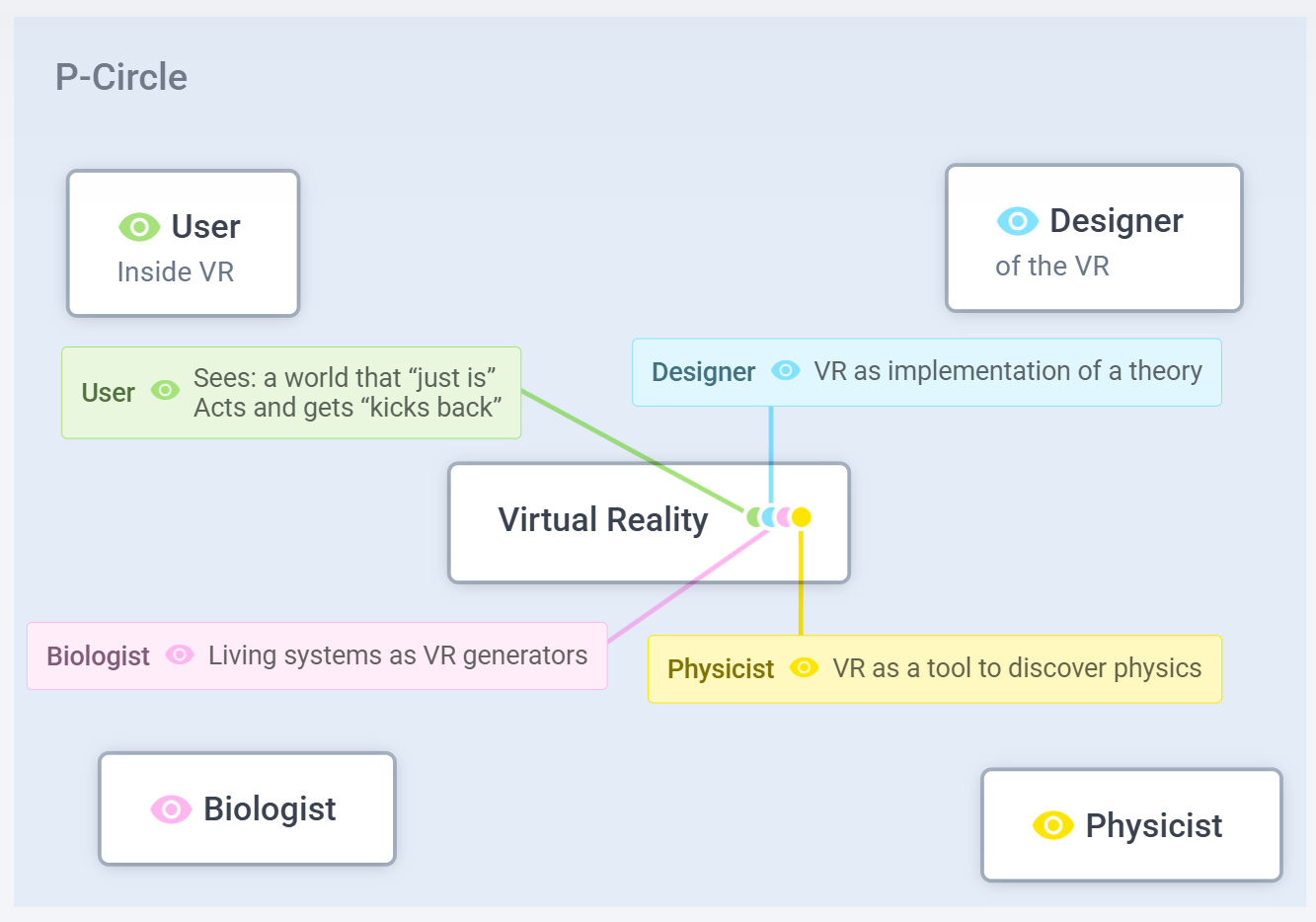

This argument sets the scene for David’s next big claim: brains are virtual reality generators and therefore, doing science can be seen as building ever more accurate virtual-reality renderings of physically possible environments.

In doing so, he’s also defending scientific realism: even if we were in a perfectly convincing simulation, our best explanations would still be about real, complex entities and laws.

Brains as Virtual Reality Generators

Now that David has argued that discovering the physics of an environment depends on being able to construct a virtual-reality rendering of it, he turns to the question of which virtual realities humans already use. His answer: the virtual reality generated by our own brains.

We can, in our minds, “render” an environment according to imagined laws of physics that differ from the true ones. Depending on how those imagined laws relate to reality, Deutsch says:

-

If the laws we use are as close as we can make them to the real laws under our constraints, we may call these renderings “applied mathematics” or “computing”.

-

If the rendered objects are very different from anything physically possible (but still logically consistent), we may call the rendering “pure mathematics”.

-

If a physically impossible environment is rendered for fun, we call it a “video game” or “computer art”.

He then broadens the point. It is not customary to think of mathematics as a form of virtual reality, but he argues that it is: the experience of doing mathematics is an external experience rendered by our brains, just like doing physics.

From there, he generalizes:

“All reasoning, all thinking and all external experience are forms of virtual reality” (p. 121)

Just to be clear: there is an objective, physical reality out there, independent of what we think or believe. But Deutsch’s point is that we never experience that reality directly:

“Every last scrap of our external experience is of virtual reality” (p. 121)

Virtual reality reconciles realism with the fact that our experience is constructed: the brain’s VR rendering is how a physical, mind-independent reality becomes knowable.

In other words, computer VR is not an exotic new thing layered on top of “real” perception. It’s the other way around: ordinary perception is one particular implementation of virtual reality, running in brains; headsets and simulations are late-coming hacks that piggy-back on that same architecture.

And he adds that:

“We shall see in Chapter 8 that all living processes involve virtual reality too, but human beings in particular have a special relationship with it” (p. 121)

So, on Deutsch’s view, logic, mathematics, philosophy, imagination, fiction, art, fantasy - and even everyday perception - are all forms of virtual reality generated by living systems, with the human brain as a particularly powerful VR generator.

Every scrap of our (mental) knowledge is encoded as programs for our brain’s own virtual-reality generator.

Conclusion

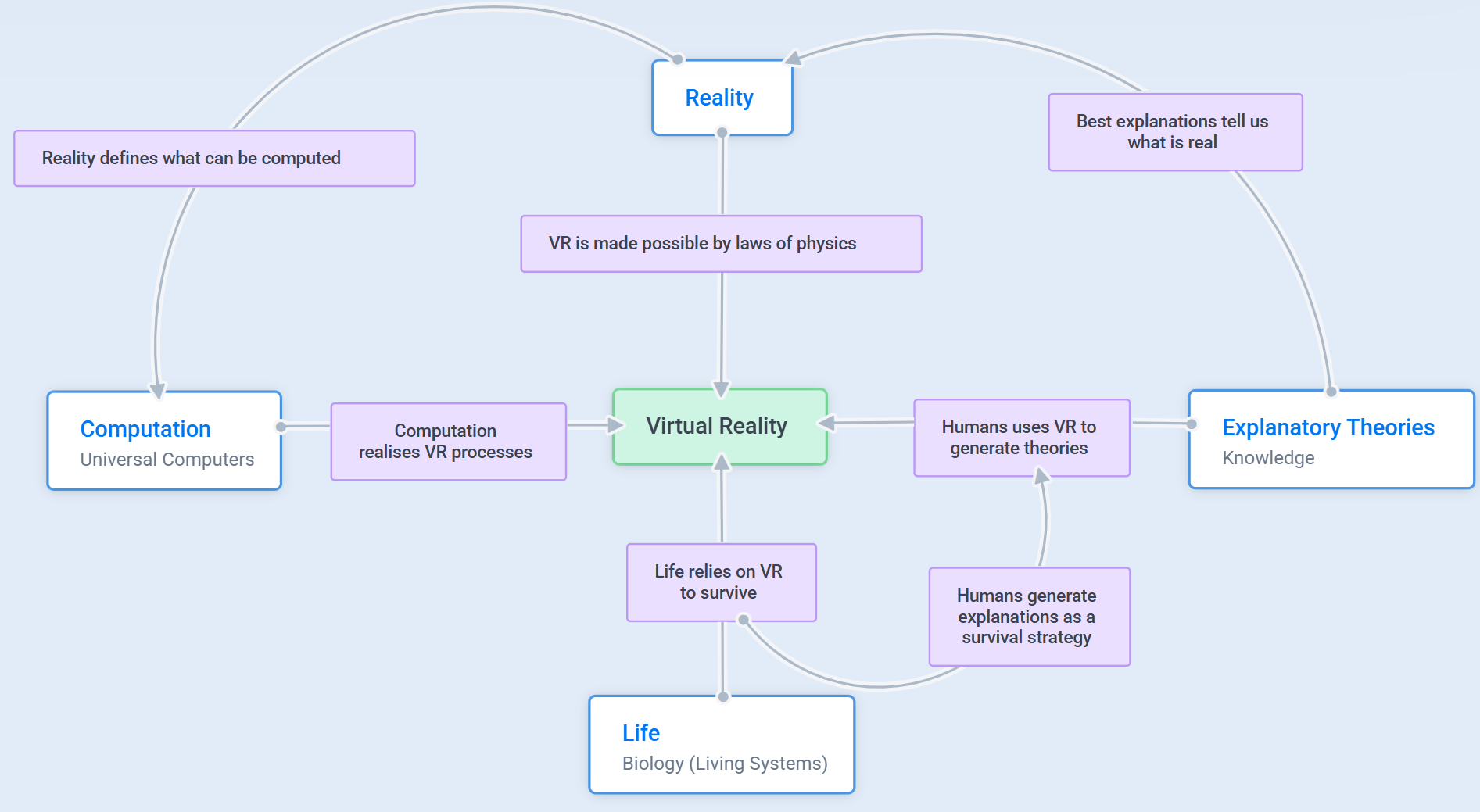

In Chapter 5, David broadens the idea of virtual reality and shows how it ties into the whole Fabric of Reality:

-

Epistemology: When someone designs a virtual reality, the program they write embodies a general, predictive theory of an environment. That links VR directly to explanatory epistemology.

-

Computation: A virtual-reality generator is, in his model, a physical process running such programs. That connects VR with the theory of universal computation.

-

Physics: Discovering the physics of an environment, he argues, depends on creating virtual-reality renderings whose behavior matches the results of all possible experiments. That connects VR with the project of fundamental physics.

-

Biology: Brains, and ultimately all living systems, function as virtual-reality generators. That connects VR with biology and the study of life. For humans in particular, he says, VR is our survival strategy: our ecological niche depends on it.

If we go back to the opening question - “Suppose that you lived inside a virtual simulation. What, if anything, in that situation should you regard as real?” - Deutsch’s answer is subtle.

First, in his sense, you already live in a kind of simulation: at the very least, in the virtual reality generated by your own brain. Every scrap of your external experience is a VR rendering, not direct access to reality.

Now push it further: what if you were also inside a perfect computer-generated simulation?

Even then, the simulator itself - its hardware, the laws it is implementing, the wider physical environment it sits in - would all be part of objective physical reality.

Your best scientific explanations would still be about real, complex entities and laws in that underlying world (even if you initially misdescribe the substrate they run on).

So being in virtual reality does not undermine realism. Reality is simply the totality of entities required by our best explanations.

This chapter sets up the next one, where Deutsch asks: What are the ultimate limits of VR? That leads straight to universality, the Turing principle, and the idea of a universal virtual-reality generator.

Systems Map

Here’s an attempt at building a system map that summarizes the key points in the chapter:

Thank you for reading. If any errors or misunderstandings appear in this article, they are entirely my own and should not be attributed to David Deutsch or his work.